Introduction of The Supreme Court’s Collegium System

- Judicial appointments in India have always been a contentious issue, with a history of tension between the judiciary and the executive.

- Recently, two key changes have brought new attention to the Supreme Court’s Collegium system: the introduction of candidate interviews and the exclusion of relatives of sitting judges from the judiciary.

- These reforms aim to make the process of judicial appointments more transparent, fair, and unbiased.

Key Developments in the Collegium System

- Interviews for Judicial Candidates: The introduction of interviews for candidates recommended for promotion to High Courts marks a significant step in improving the transparency and fairness of the judicial appointment process. The Collegium will now directly engage with candidates, allowing them to better assess their qualifications and suitability for higher judicial positions. This reform ensures that the selection process is more thorough and personal.:

- Exclusion of Relatives of Sitting Judges To address concerns of nepotism, the Collegium has decided to exclude candidates whose close family members have been or are currently judges in the High Courts or Supreme Court. This move aims to diversify the judiciary and prevent the concentration of power within select families, ensuring a more merit-based and equitable process.

Read also: Great Nicobar Island Development Project – UPSC Study Guide

Why These Changes Matter

- These reforms are pivotal in addressing the long-standing issues of transparency, accountability, and diversity in the judiciary.

- By making these adjustments, the Collegium hopes to restore public trust in the judicial appointments system, ensuring it is open, fair, and free from favoritism.

Constitutional Provisions for Judicial Appointments

- Article 124 (2): This article mandates that judges of the Supreme Court are appointed by the President, after consulting with the Chief Justice of India (CJI) and other relevant judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts, as necessary. The CJI must be consulted for all appointments, except for the Chief Justice of India.

- Article 217: Similar to Article 124, this article governs the appointment of High Court judges, requiring consultation with the CJI, the Governor of the state, and the Chief Justice of the High Court concerned.

Evolution of the Judicial Appointment System in India

- During Colonial Rule: Under British colonial rule, the executive had complete control over judicial appointments, limiting the judiciary’s independence. This system was heavily criticized and became a central issue when India gained independence, as it threatened the autonomy of the judiciary.

- Constitutional Debates: The framers of the Indian Constitution sought to strike a balance between the judiciary’s independence and the executive’s role in judicial appointments. Articles 124 and 217 were specifically designed to ensure that appointments would not be influenced by political considerations, while also safeguarding judicial independence.

- Landmark Judicial Interventions: The current system of judicial appointments evolved through a series of landmark Supreme Court judgments known as the Judges’ Cases:

- First Judges Case (1981): The Supreme Court ruled that the word “consultation” in Article 124 does not mean “concurrence,” allowing the President to make judicial appointments without being bound by the Chief Justice of India’s advice.

- Second Judges Case (1993): This landmark ruling reversed the First Judges Case and affirmed that “consultation” does, in fact, mean “concurrence.” The Court mandated that judicial appointments should be made by a collegium of the Chief Justice of India and the two senior-most Supreme Court judges.

- Third Judges Case (1998): In this ruling, the Court expanded the collegium to five members, consisting of the Chief Justice of India and the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, cementing judicial control over the appointment process.

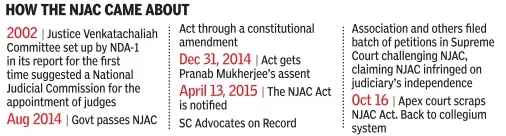

The National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC)

- In 2014, the 99th Constitutional Amendment Act proposed the creation of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) to replace the Collegium system. The NJAC aimed to bring more transparency, inclusivity, and accountability to the judicial appointments process.

- NJAC Composition:

- The NJAC was designed to be a six-member body, including:

- The Chief Justice of India as the ex-officio Chairperson.

- Two senior-most Supreme Court judges.

- The Union Law Minister.

- Two eminent persons from civil society (with one representative from SC/ST/OBC/minorities or women).

- The Fourth Judges Case (2015): In 2015, the Supreme Court declared the 99th Constitutional Amendment and NJAC Act unconstitutional, reaffirming the Collegium system and asserting that the NJAC violated the basic structure of the Indian Constitution by undermining judicial independence.

Key Issues with NJAC

- Lack of Legal Expertise: Critics argued that the two eminent persons could be appointed without legal qualifications, potentially leading to politically influenced decisions.

- Veto Power: The ability for any two members of the NJAC to veto judicial recommendations raised concerns about undermining judicial independence. In 2015, the Supreme Court struck down the NJAC Act, expressing that the veto power could have allowed the executive to interfere with judicial independence.

- Ambiguity in Criteria: Some provisions, such as the criteria for appointing the Chief Justice of India, were left undefined, creating uncertainty in the process. Section 5(1) of the NJAC Act required the NJAC to recommend the senior-most judge of the Supreme Court for the position of Chief Justice of India “if he is considered fit to hold the office.” However, the term “fit” was not defined. This ambiguity left the door open for subjective assessments, creating a space for potential bias or arbitrary rejection of the senior-most judge without sufficient legal basis.

- No Casting Vote: The lack of a casting vote for the CJI in the event of a tie was seen as a potential cause for deadlocks in decision-making.

- Executive Overreach: Critics pointed out that Section 12 of the NJAC Act allowed Parliament to frame laws that could potentially nullify or override regulations established by the NJAC regarding judicial appointments. This provision would have allowed the executive and legislative branches of the government to wield significant control over judicial appointments, undermining the independence of the judiciary.

- Politicization of Judicial Appointments: Critics argued that by including the Union Law Minister as an ex-officio member and two eminent persons, NJAC could politicize the process of judicial appointments. In the case of Justice P.D. Dinakaran, who faced allegations of corruption and impropriety, the government delayed action for a long time.

- No Clear Accountability: While the NJAC was intended to bring transparency, it was criticized for not having a well-defined accountability mechanism for the decisions made by its members, particularly the executive appointees. The controversial appointment of Justice Ashok Kumar in the Madras High Court raised concerns about judicial accountability. Justice Kumar’s appointment was questioned due to his proximity to political leaders.

- Fear of Judicial Insubordination: Another criticism was that the NJAC, by giving the executive a role in judicial appointments, could create a situation where judges might feel beholden to the government for their elevation, thereby compromising their ability to rule impartially in cases involving the government. The ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla (1976) case, also known as the Habeas Corpus case, is a striking example where the majority of the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the government’s arbitrary detention powers during the Emergency.

The Current System of Judicial Appointments in India

- After the judicial intervention in the Judges’ Cases, the Collegium System became the established procedure for judicial appointments and transfers.

- The Collegium is composed of the Chief Justice of India and the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.

- While the executive conducts background checks, the final recommendations are made by the Collegium.

- If the government objects to a recommendation, it can return the proposal for reconsideration. If the Collegium reiterates its recommendation, the government must comply.

Advantages of the Collegium System

- Ensures Judicial Independence: By insulating the judiciary from political and executive influence, the Collegium system safeguards the independence of the judiciary, ensuring that judges can make impartial decisions.

- Example: In the case of S.P. Gupta v. Union of India (1981), also known as the First Judges Case, the court upheld the executive’s power in judicial appointments.

- This resulted in concerns about executive interference in appointments. The collegium system, later introduced by the Second and Third Judges cases, rectified this by giving primacy to the judiciary in appointments, thus preventing a repeat of such executive dominance.

- Prevents Executive Bias: Given that the government is often the primary litigant, its influence over judicial appointments could impair judicial impartiality.

- The 2G Spectrum Case (2012), which involved several high-ranking government officials, was adjudicated impartially by judges who were appointed through the collegium system. The decision resulted in the cancellation of 122 telecom licenses, showing that even in cases involving the government, the judiciary was capable of delivering an independent and unbiased verdict.

- Expertise in Selection: Judges, as legal experts, are better equipped than politicians or bureaucrats to assess the qualifications and suitability of judicial candidates.

- The appointment of Justice U.U. Lalit to the Supreme Court, a former senior advocate with extensive expertise in criminal law, was facilitated by the collegium system. His legal acumen was evident in landmark cases such as Ayodhya Verdict (2019), where he played a key role in resolving one of India’s most contentious legal disputes.

- Safeguards Constitutional Rights: The system ensures that the judiciary remains independent and committed to upholding fundamental rights, such as the Right to Life and Privacy.

- In Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018), the Supreme Court decriminalized Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalized same-sex relations. The decision, made by judges appointed through the collegium system, was critical for upholding democratic values and protecting individual rights.

- Reduces the Risk of Politicization: By removing executive control from the appointment process, the collegium system reduces the risk of appointments being politically motivated, ensuring that only judicial merit is considered.

- During the tenure of Justice Altamas Kabir, who was appointed via the collegium, the judiciary maintained its independence in several cases involving the executive. In the Coalgate scam case (2012) ,the Supreme Court canceled coal block allocations by the government.

- Promotes Judicial Diversity: The collegium system, by focusing on merit and qualifications, has been instrumental in promoting diversity within the judiciary, ensuring that judges from different regions, genders, and social backgrounds are appointed.

-

- The collegium’s appointment of Justice Indu Malhotra directly from the bar in 2018, made her the first woman lawyer to be elevated to the Supreme Court.

Challenges with the Collegium System

- No Constitutional Backing: The collegium system was established through judicial interpretations in the Second and Third Judges cases but is not explicitly enshrined in the Constitution. Article 124 of the Indian Constitution only mentions “consultation” with the Chief Justice of India for appointments, not “concurrence,” as later interpreted by the judiciary.

- Opaque Procedures: The collegium system lacks formal procedures for the selection process, and decisions on appointments and rejections are not made public. There is no clear explanation of the criteria used for selecting or rejecting candidates, leaving the process shrouded in secrecy.

- In 2014, the collegium’s recommendation to elevate Justice Gopal Subramanium to the Supreme Court was withdrawn after the government raised objections, but no detailed reasons were provided to the public.

- Perception of Undemocratic Practices: The collegium system, where judges appoint judges, is often seen as undemocratic because it lacks external oversight from either the executive or the legislature.

- In the 2018 controversy surrounding the appointment of Justice K.M. Joseph, the collegium had to reconsider its initial recommendation after the government sent it back, raising concerns about accountability. While the collegium later reiterated its recommendation, the process brought attention to the need for greater accountability and transparency in how such decisions are made.

- Favoritism in Appointments: One of the major criticisms of the collegium system is the allegation that it has led to nepotism, where relatives and close associates of sitting judges are appointed to high judicial positions, giving rise to claims of “uncle judges” and favoritism.

- For instance, in the Delhi High Court, there have been allegations of nepotism, where relatives of judges were appointed to the judiciary, raising concerns about fairness and transparency in appointments.

- Absence of Global Parallels: Unlike in most other democracies, where judicial appointments involve a mix of input from the executive, legislature, and judiciary, India’s collegium system gives the judiciary complete control over the process. Critics argue that this is an anomaly, and the lack of external input can lead to insularity and groupthink.

See more: A List of Major Freedom Fighters of India (1857-1947)

Global Best Practices in Judicial Appointments

In comparison to India’s system, many countries use a more balanced approach involving both judicial and executive participation in the appointment of judges.

- United Kingdom: The Constitutional Reform Act of 2005 established a Judicial Appointments Commission with representation from both the judiciary and the executive to ensure impartiality and transparency in judicial appointments.

- South Africa: The Judicial Service Commission (JSC) advises the President on judicial appointments, ensuring diverse representation from all branches of government.

- France: Judicial appointments are made by the High Council of the Judiciary (Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature), which consults with the Minister of Justice, ensuring a balanced and representative approach to judicial selection.

Way Forward

- Reforming NJAC: The NJAC can be revisited by addressing its flaws, such as veto power and unclear membership criteria. A reformed NJAC should involve feedback from all stakeholders, including the judiciary, the executive, and civil society.

- Finalizing the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP): The judiciary and government must work together to finalize a MoP that sets clear, transparent guidelines for judicial appointments, including eligibility criteria and procedures for complaints against candidates.

- Enhancing Transparency: The judiciary must disclose the reasons for accepting or rejecting candidates, as well as the parameters considered for selection.

- Implementing All India Judicial Services (AIJS): Establishing AIJS could help improve the quality of judges in lower courts and should be implemented after reaching a consensus among all stakeholders.

- Independent Secretariat for Judicial Appointments: An independent secretariat should be established to manage judicial appointments efficiently. This would include a comprehensive database of candidates and ensure that judicial vacancies are filled in a timely manner.