Introduction

- The recent controversy surrounding the Tirupati Laddu Prasadam has reignited the debate on state control of temples in India.

- This control began post-independence with the state of Tamil Nadu (then Madras), which introduced legislation to bring temples under state oversight. Currently, several other states, including Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha, Maharashtra, Himachal Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan, have enacted laws to manage Hindu temples.

- However, these laws have faced criticism from various Hindu religious organizations, who argue that temples are being treated as sources of revenue, and that temple boards lack adequate representation. This article explores the ongoing issue of state control over temples in India.

Historical Overview of State Control of Temples in India

Colonial Period:

Legislative Framework by the East India Company (1810-1817):

-

- In the early 19th century, the East India Company introduced laws in regions like Bengal, Madras, and Bombay.

- These laws aimed to regulate temple administration, primarily to curb the misappropriation of temple funds.

- This marked the beginning of state intervention in temple management, setting a precedent for future regulations.

Read also: University Ranking Framework: A Comprehensive Guide | UPSC

Religious Endowments Act (1863):

-

- The British government enacted the Religious Endowments Act, which sought to secularize temple management.

- It transferred control from traditional authorities to newly formed committees. However, despite this decentralization, the British government retained significant influence through existing legal frameworks such as the Civil Procedure Code and the Charitable and Religious Trusts Act of 1920.

- This dual control ensured that the government could intervene in temple affairs when deemed necessary.

Madras Hindu Religious Endowments Act (1925):

-

- This act established the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Board in Madras, which created a statutory body for temple management.

- It empowered provincial governments to legislate on temple matters and instituted a board of commissioners to oversee temple affairs, further institutionalizing state control over religious practices.

Post-Independence Period:

Recommendations by the Law Commission of India:

-

- After independence, the Law Commission emphasized the need for legislation to prevent the misuse of temple funds.

- This reflected a growing concern about the management of religious endowments and the potential for corruption, prompting further legislative actions to ensure transparency and accountability.

Tamil Nadu Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (TN HR&CE) Act, 1951:

-

- The TN HR&CE Act established a dedicated Department of Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments in Tamil Nadu.

- This department was tasked with the administration, protection, and preservation of temples and their properties, marking a significant step in formalizing state control over temple management in one of India’s most religiously active states.

Bihar Hindu Religious Trusts Act, 1950:

-

- Similarly, Bihar introduced the Hindu Religious Trusts Act to regulate religious institutions in the state.

- This act aimed to oversee the operations of temples and manage the funds associated with them, reinforcing the notion that state oversight was essential for the proper functioning of religious organizations.

Constitutional Provision for State Control of Temples

-

- Article 25(2): This article grants the state the authority to regulate the economic, financial, political, or secular aspects associated with religious practices. It also allows the state to enact laws aimed at social welfare and reform, as well as to ensure Hindu religious institutions are accessible to all classes of Hindus.

- Seventh Schedule: Religious endowments and institutions are included in the Concurrent List of the Seventh Schedule, enabling both the Central and State governments to legislate on matters related to them.

Judicial Precedents Supporting State Control Over Temple Management

Shirur Mutt vs. The Commissioner, Hindu Religious Endowments, Madras (1954):

-

- The Supreme Court of India established a significant precedent by affirming that the state possesses the authority to regulate the administration of religious and charitable institutions. This case underscored the balance between religious freedoms and the necessity for governmental oversight.

Ratilal Panachand Gandhi v. State of Bombay (1954):

-

- In this landmark decision, the Supreme Court reiterated that the state has the power to regulate the administration of trust properties. This ruling reinforced the notion that effective governance of religious trusts is essential for preventing misuse and ensuring accountability.

Pannalal Bansilal Pitti vs. State of Andhra Pradesh (1996):

-

- The Supreme Court upheld legislation that abolished hereditary rights over temple management. It emphasized that such laws do not need to apply equally across all religions, thus affirming the state’s role in reforming outdated practices in temple administration.

Arguments in Favor of State Control of Temples in India

-

- Prevention of Temple Mismanagement: A primary argument for state control is the enhancement of transparency in temple administration. Government oversight is crucial for reducing the risks of misappropriation and corruption, ensuring that temple funds are managed responsibly and ethically.

- For example, in Tamil Nadu, the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HRCE) Department conducts audits of temple finances to ensure accountability. Reports of mismanagement in temples have prompted state intervention to investigate and rectify issues, thereby fostering responsible management of temple funds.

- Protection from Commercialization: State involvement aims to prevent the commercialization of religious practices and protect temples from exploitation by vested interests. By regulating finances, the government ensures that temple activities remain focused on spiritual and community welfare rather than profit motives.

- A notable case is the Kumaraswamy Temple in Karnataka, where state regulations have curtailed commercial activities like sale of prasad at exorbitant prices by unauthorized vendors. State regulations have aimed to standardize the pricing of prasad and limit commercial sales to ensure that devotees are not exploited.

- Promotion of Gender Equality: State management seeks to make temple services and resources accessible to all devotees, irrespective of gender. For instance, the Travancore Devaswom Board played a pivotal role in supporting equitable access for women in the Sabarimala Temple entry case, advocating for gender inclusivity in religious practices.

- Redistribution of Resources: The revenue generated from temples is often redirected towards state initiatives that benefit the broader community. For example, the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HRCE) Department of Tamil Nadu utilizes temple funds to establish schools, colleges, and hospitals, thereby promoting community development.

- Religious and Cultural Inclusivity: State control helps ensure that temples adhere to constitutional principles of inclusivity for marginalized communities. In Tamil Nadu, the HRCE Department has worked to ensure temple entry for Dalits and other backward communities in several temples that historically restricted access.

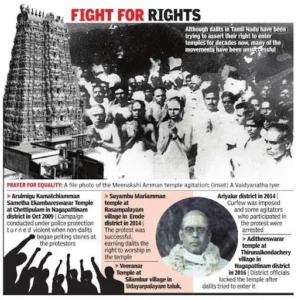

- Also, in Meenakshi Amman Temple, the government intervention facilitated the entry of Dalits, allowing for greater inclusivity and representation in temple rituals and activities.

- Prevention of Exploitation of Devotees: Government regulation aims to protect devotees from exploitation by temple authorities, such as the imposition of exorbitant fees for rituals or burdensome financial practices. For instance, many temples in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh have established guidelines for fees associated with rituals and offerings to safeguard the interests of devotees.

- The Tirupati Tirumala Devasthanams has implemented standardized fees for various services, ensuring transparency and fairness in the costs incurred by devotees, thereby safeguarding their interests.

Vaikom Satyagraha

|

Arguments Against State Control of Temples in India

Unfair Treatment:

-

- Critics argue that the government disproportionately targets Hindu temples for control while allowing other religious institutions, such as mosques, churches, and gurdwaras, to manage their own affairs independently. This perceived bias raises questions about the equality of treatment among different religious groups.

- For instance, similar to Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra has the Maharashtra Hindu Religious and Charitable Institutions Act (1959), which governs Hindu temples and mandates state control over their administration. In contrast, there are no corresponding laws specifically regulating the administration of mosques or churches in the state, allowing those religious institutions greater autonomy.

Mismanagement and Bureaucratic Inefficiency:

-

- Government-appointed boards and officials often lack the necessary expertise and commitment to effectively manage temple affairs. This inadequacy can lead to mismanagement and bureaucratic inefficiencies.

- In 2018, devotees of the Chidambaram Nataraja Temple expressed their frustration over the mismanagement of funds collected for temple renovations. Reports indicated that while donations were being collected for specific purposes, the HRCE Department had diverted these funds for unrelated administrative expenses, leading to allegations of corruption and negligence in addressing the temple’s actual needs.

Diversion of Temple Funds:

-

- There is significant opposition from devotees regarding the diversion of temple funds for secular activities. Protests have erupted against the use of religious funds for purposes not aligned with the spiritual mission of the temples, highlighting concerns over financial priorities and transparency.

- A notable example is the controversy surrounding the Sri Kalahasti Temple in Andhra Pradesh, where devotees protested the allocation of temple funds for state-sponsored infrastructure projects rather than for temple maintenance or community welfare initiatives.

Erosion of Temple Heritage and Traditions:

-

- The imposition of administrative norms by the state, which may not align with the spiritual and ritualistic aspects of temple management, can lead to the erosion of temple heritage and traditions. For instance, the government’s support for women’s entry into the Sabarimala Temple has clashed with the temple’s longstanding ritualistic practices.

Decline in Devotee Trust and Participation:

-

- Critics assert that bureaucratic control diminishes the trust and participation of devotees in temple management. This disengagement can undermine the communal spirit and diminish the role of local traditions in temple affairs. A study conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) in 2021 revealed that around 60% of respondents felt disconnected from temple management due to the centralization of control by the HRCE Department.

Economic Mismanagement of Temple Assets:

-

- In states like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, reports of encroachments on temple land by private individuals or government entities have raised serious concerns regarding the economic mismanagement of temple resources. Such instances exacerbate fears about the effectiveness of state oversight.

- One notable case involving allegations of encroachments on temple land in Karnataka is the Sri Lakshmi Narasimha Swamy Temple Case in Bengaluru.

Better Management through Private Trusts:

-

- Critics point to successful private trusts, like the Shirdi Sai Baba Temple Trust in Maharashtra, which efficiently run charitable hospitals, schools, and community programs. This success suggests that temples might be better managed outside of state control.

Read also: Overwork in India: Threat to Employee Health & Productivity | UPSC

Way Forward

-

- Greater Autonomy with Oversight: Establish independent temple trusts that include local religious leaders, community representatives, and legal or financial experts. The government’s role should be limited to oversight rather than direct management. A model to consider is the management of the Golden Temple by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), which operates independently of state control.

- Increased Transparency and Accountability: Introduce an independent auditing body to conduct regular financial audits of temples. Additionally, mandating public disclosure of temple funds would enhance accountability and build trust within the community.

- Formation of Devotee Councils: Establish local councils composed of devotees and community leaders to provide advisory input on temple management, rituals, and festivals. Empowering the community in this way can help safeguard the religious and cultural traditions of the temple.

- Government as a Custodian of Heritage, Not Manager: Shift the state’s role from that of a manager to a custodian responsible for preserving the heritage and architecture of ancient temples. This change would allow for the protection of cultural assets without direct interference in temple management.

- Collaboration with Religious Leaders: While temple funds can be utilized for social welfare programs such as healthcare, education, and poverty alleviation, this should be done only after consulting with temple authorities and religious leaders. Collaborative efforts can ensure that community needs are met while respecting religious sentiments.