Introduction

- The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in India has introduced draft guidelines to facilitate the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment for terminally ill patients.

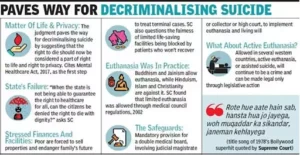

- These guidelines come in the wake of Supreme Court rulings in 2018 and 2023, which recognized the right to die with dignity.

- With a focus on patient rights and compassionate care, the guidelines aim to provide a structured legal framework that protects patients, families, and medical professionals involved in end-of-life care decisions.

What Does Withholding or Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatment Mean?

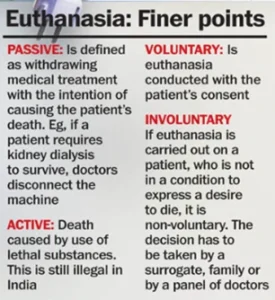

- Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment involves discontinuing medical interventions such as ventilators and feeding tubes, especially when they no longer improve the patient’s condition and may only prolong suffering. This decision aligns with ethical principles in palliative care, prioritizing comfort and pain relief over life extension when recovery is no longer feasible.

- How Withholding Life Support Works in India?

- Informed Refusal: Patients with the capacity to make informed choices can refuse life-sustaining treatment, exercising their autonomy and right to control their own medical care.

- Advance Medical Directive or Living Will: Patients may create a ‘living will,’ specifying their preferred medical treatments if they become incapacitated and unable to communicate their wishes.

- Physician’s Determination in Absence of Living Will: When no advance directive exists, the treating physician may recommend withdrawal of life support based on the patient’s condition:

-

- No Realistic Chance of Recovery: Life-sustaining treatment may be discontinued if the patient is in a terminal condition or vegetative state with little hope of recovery.

- Artificially Prolonging Dying: If continuing treatment would only extend the dying process without therapeutic benefit, withdrawal may be deemed appropriate.

-

- Importantly, this transition from life support to palliative care does not equate to abandonment. Instead, it signifies a shift toward providing comfort, minimizing pain, and respecting the patient’s dignity at the end of life.

Read also: BRICS Plus: Global Influence and Economic Collaboration | UPSC

Evolution of the Right to Die in India

- India’s journey toward recognizing the right to die with dignity has evolved through significant Supreme Court rulings:

- Aruna Shanbaug v. Union of India (2011): In this landmark case, the Supreme Court recognized the right to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment for patients without decision-making capacity under specific circumstances.

- Common Cause v. Union of India (2018): The Supreme Court expanded the right to die with dignity under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. This ruling also legalized advance medical directives, allowing individuals to make end-of-life decisions in advance.

- Common Cause v. Union of India (2023): This judgment simplified the process of creating living wills by removing bureaucratic barriers, empowering more people to document their end-of-life preferences.

Key Provisions in the New Guidelines for Withdrawing Life Support

- The Ministry’s guidelines introduce a detailed framework for withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, establishing medical boards and a series of protocols to ensure legal, ethical, and transparent processes.

- Definition: The Terminal illness in the draft guidelines has been defined as an irreversible or incurable condition from which death is inevitable in the foreseeable future. Severe devastating traumatic brain injury which shows no recovery after 72 hours or more is also included.

- Establishment of Medical Boards:

-

- Primary Medical Board: Comprising the treating physician and two subject-matter experts with at least five years of experience, this board assesses the patient’s condition to determine the appropriateness of life-support withdrawal.

- Secondary Medical Board: A Secondary Medical Board (SMB) of 3 physicians with one appointee by the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of the district must validate the decision by the PMB.

-

- Consent from Nominated Individuals: When a patient has a living will or designated representative, the nominated person provides consent for life-support withdrawal. In the absence of a directive, family members or surrogate decision-makers must consent, enabling a shared and compassionate decision-making process.

- Notification to Judicial Magistrate: Hospitals must notify a judicial magistrate about decisions to withdraw life support, ensuring accountability and compliance with legal standards.

- Time Limits and Verification Processes: The DGHS has also introduced a preferable 48-hour time limit for both the primary and secondary medical boards to provide their opinions. This ensures that terminally ill patients receive timely decisions regarding their care, minimising prolonged suffering and uncertainty.

- Do-Not-Attempt-Resuscitation (DNAR) Orders: The guidelines explicitly address DNAR orders for the first time, allowing doctors to refrain from CPR in cases where there is no realistic chance of survival. This addition underscores the broader aim of minimising unnecessary interventions that may only prolong suffering.

Significance of the Guidelines

- Affirming the Right to Die with Dignity: These guidelines operationalize the Supreme Court’s landmark rulings, legally empowering terminally ill patients to make dignified end-of-life choices in a structured manner.

- Transparent and Structured Decision-Making: The formation of Primary and Secondary Medical Boards ensures that decisions around life-support withdrawal are made transparently, with medical expertise and independent reviews.

- Clear Protocols for Withdrawal of Life Support: With specific steps involving board assessments, consent from family or surrogates, and notification to a magistrate, the guidelines offer a transparent, multi-layered process that protects the interests of patients and families alike.

- Ethical Shared Decision-Making: By fostering collaboration between healthcare providers and families, the guidelines ensure that decisions are compassionate and respectful of the patient’s wishes and values, promoting patient autonomy and reducing the emotional burden on families.

Challenges in Implementing the Life-Support Withdrawal Guidelines

- Complexity in Medical Board Setup: Establishing Primary and Secondary Medical Boards across hospitals may prove challenging, especially for smaller or rural hospitals with limited resources.

- Lack of Dedicated Legislation: While the guidelines provide structure, the absence of a specific law governing life-support withdrawal may lead to inconsistent implementation and legal uncertainty, potentially deterring hospitals from full compliance.

- Cultural Misunderstandings: Terms like “Passive Euthanasia in India” and societal discomfort around the right to die can hinder the acceptance of life-support withdrawal, presenting a significant barrier.

- Intricacies of the Living Will Process: Creating a living will is a lengthy process requiring documentation, witnesses, and notarization, which can discourage patients from completing this vital step in planning end-of-life care.

- Delays Due to Multi-Step Process: The requirement for multiple layers of evaluation, consent, and judicial notification can delay life-support withdrawal, potentially affecting the patient’s right to die with dignity.

- Emotional Strain on Families and Physicians: The emphasis on shared decision-making, while safeguarding patient rights, places substantial emotional strain on families and healthcare providers, complicating the end-of-life decision-making process.

Global Perspectives on Euthanasia and Assisted Dying

Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg:

-

- Both active euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are legal, subject to stringent regulations.

- Patients must demonstrate unbearable suffering with no possibility of recovery.

- Multiple medical evaluations are required to confirm eligibility.

- In the Netherlands, minors aged 12-17 can request euthanasia with parental consent.

Switzerland:

-

- Physician-assisted suicide is legal, and services are available through organizations such as Dignitas.

- Switzerland allows non-residents to seek assisted dying, attracting both global criticism and admiration.

Canada:

-

- Introduced Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) in 2016, permitting physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia under strict conditions.

- Canadian law mandates a waiting period, multiple assessments, and procedural safeguards to ensure that the patient’s request is fully informed and voluntary(

United States:

-

- States like Oregon, Washington, and California have implemented “Death with Dignity” laws, permitting physician-assisted suicide for terminally ill patients.

- However, these laws do not permit active euthanasia, where a physician directly administers the means to cause death.

- The variability across U.S. states reflects the complex interplay between state rights, individual autonomy, and ethical considerations, mirroring some of the challenges India faces as it implements its Passive Euthanasia guidelines.

Read also: Global Supply Chain Management: Challenges & Strategies | UPSC

Way Forward

- Legislative Clarity: A dedicated law governing life-support withdrawal in terminally ill cases would reduce inconsistencies, reinforce the right to die with dignity, and provide legal clarity across healthcare institutions.

- Medical Training and Education: Providing healthcare professionals with thorough training on the ethical, procedural, and legal aspects of life-support withdrawal will promote compassionate and consistent practices across the country.

- Simplifying the Living Will Process: Streamlining the documentation and notarization requirements for living wills would make it easier for people from diverse backgrounds to access this right.

- Public Awareness Campaigns: Educating the public about the right to die with dignity can empower patients and families to make informed decisions, aligning with their values and alleviating unnecessary suffering.

- Enhancing Palliative Care Infrastructure: Expanding palliative care services, especially in rural and smaller healthcare facilities, can support the practical implementation of these guidelines, ensuring that dignified end-of-life care is accessible to all.