Introduction

- The judiciary forms the backbone of any democracy, safeguarding constitutional values, ensuring justice, and upholding the rule of law.

- In India, judges, especially those in the Supreme Court and High Courts, play an essential role in maintaining the integrity of the judicial system.

- However, when a judge’s conduct or capacity to perform their duties is called into question, the Constitution of India provides a strict framework for their removal through impeachment.

- This process recently came into the spotlight with the Opposition INDIA bloc parties in the Rajya Sabha initiating a motion to impeach Justice Shekhar Kumar Yadav of the Allahabad High Court for alleged controversial remarks against minorities.

Constitutional Provisions for the Impeachment of Judges in India

- While the term “impeachment” is not explicitly mentioned in the Indian Constitution, the process for the removal of judges is outlined under Articles 124, 217, and 218.

- These provisions allow for the removal of judges on grounds of “misbehaviour” or “incapacity.”

- The provisions governing the impeachment of Supreme Court and High Court judges are as follows:

- Article 124(4) and (5): These apply to the removal of a judge from the Supreme Court.

- Article 217(1)(b) and Article 218: These provisions apply to the removal of a judge from a High Court.

- Although the Constitution does not explicitly mention impeachment as such, it follows a procedure similar to that used for the impeachment of the President under Article 61, where the process involves both Houses of Parliament.

Read also: India’s Space Sector: Key Insights for UPSC Preparation

Grounds for Removal of Judges

- The Constitution permits the removal of judges only on the grounds of “proved misbehaviour” or “incapacity.” However, the terms are not clearly defined, which can lead to subjective interpretations. The key grounds for removal include:

- Proved Misbehaviour: This refers to actions or conduct that violate the ethical standards and expectations of a judge. Since the term is vague, it can be interpreted in various ways, which raises concerns about potential misuse.

- Incapacity: This includes physical or mental incapacity that affects the judge’s ability to perform their duties effectively. The Constitution does not specify the exact criteria for incapacity, leaving room for subjective interpretation.

- To initiate the removal process, the motion must be passed by both Houses of Parliament with:

- A majority of the total membership of each House.

- A two-thirds majority of those present and voting.

- Once Parliament approves the motion, the President is required to issue an order for the judge’s removal.

Procedure for Impeachment of Judges

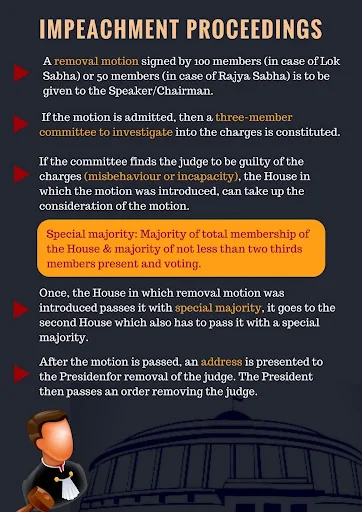

- The process for removing a judge from office is outlined in the Judges Inquiry Act, 1968, and the Judges Inquiry Rules, 1969. The procedure includes several key steps:

- Initiation of Motion: A notice of motion, signed by at least 100 Lok Sabha members or 50 Rajya Sabha members, is submitted to the Speaker of the Lok Sabha or the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha, depending on where the motion originates.

- Admittance of Motion: The Speaker or Chairman examines the motion and decides whether to admit it. If the motion is admitted, a three-member inquiry committee is constituted.

- Inquiry Committee: The committee is composed of:

- The Chief Justice of India (or a Supreme Court judge),

- The Chief Justice of a High Court, and

- A distinguished jurist, as appointed by the Speaker or Chairman.

- This committee investigates the charges, collects evidence, and examines witnesses.

- Committee Findings: After the inquiry, the committee submits its report to the Speaker or Chairman. If the charges are not substantiated, the process ends. If the charges are proven, the motion proceeds to the originating House of Parliament.

- Parliamentary Voting: Both Houses of Parliament must approve the motion. The motion requires:

- A majority of the total membership of each House,

- A two-thirds majority of those present and voting in both Houses.

- Presidential Order: If both Houses approve the motion, the President is required to issue an order for the judge’s removal.

Impeachment Attempts in India: Key Instances

- Justice V. Ramaswami (1993): Accused of financial impropriety, Justice Ramaswami faced an impeachment motion. Despite the inquiry committee finding him guilty, the motion failed due to political considerations, particularly the Congress party’s abstention from voting.

- Justice Soumitra Sen (2011): Justice Sen was accused of misappropriating funds. The Rajya Sabha impeached him, but he resigned before the Lok Sabha could act on the motion, bringing the process to a halt.

- Justice S. K. Gangele (2015): Allegations of sexual harassment were made against Justice Gangele. However, the inquiry committee cleared him of any wrongdoing.

- Justice C.V. Nagarjuna (2017): Allegations of financial misconduct and victimizing a Dalit judge were raised against Justice Nagarjuna, but the motion failed as MPs withdrew their signatures.

- Justice Dipak Misra (2018): An impeachment motion was filed against Justice Misra, the former Chief Justice of India, but it was rejected at the preliminary stage by the Rajya Sabha Chairman.

Impeachment Procedures in Other Countries

- United Kingdom: Judges hold office during “good behaviour” and can be removed by the Crown following an address from both Houses of Parliament. Misconduct allegations are investigated by a tribunal or the Office for Judicial Complaints, which then advises the Lord Chancellor before Parliament acts.

- United States: Federal judges serve during “good behaviour,” according to Article III of the U.S. Constitution. Only Congress has the authority to remove a judge, through a vote of impeachment in the House and a trial and conviction by the Senate.

- Canada: Judges in Canada serve during “good behaviour” and can be removed by the Governor General following an address by both the Senate and the House of Commons. Grounds for removal include misconduct, age, infirmity, or failure to perform their duties.

Limitations of the Impeachment Process in India

- Party Whip and Anti-Defection Law: The anti-defection law mandates MPs to follow party lines, which may stifle independent judgment in cases of impeachment.

- Resignation Loophole: Judges can evade impeachment by resigning before the process concludes, as demonstrated in the case of Justice Soumitra Sen.

- Ambiguity in Grounds for Removal: Terms such as “misbehaviour” and “incapacity” are not well-defined, leading to subjective interpretations that can be misused.

- Political Influence: The process depends on parliamentary approval, which can be influenced by political considerations, as seen in the case of Justice Ramaswami, where political dynamics played a key role in the failure of the impeachment motion.

- Transfer Instead of Inquiry: Allegations against judges are sometimes resolved through transfers rather than a proper inquiry, undermining the accountability system.

See more: North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO): Origin & Mandate | UPSC

Way Forward

- Closing the Resignation Loophole: Laws should be amended to ensure that allegations against a judge are still investigated even if the judge resigns, preventing resignation from becoming an escape route.

- Promoting Judicial Accountability: A culture of accountability within the judiciary, supported by regular performance reviews and internal transparency mechanisms, would reduce the need for impeachment and ensure better conduct among judges.

- Strengthening Inquiry Mechanisms: Inquiry processes should be strengthened by introducing stricter timelines and safeguards to ensure impartial and timely investigations.

- Clarifying Grounds for Removal: The vague terms “misbehaviour” and “incapacity” should be clearly defined in the Constitution to prevent subjective interpretations and misuse.

- Establishing an Independent Body: Creating an independent commission, similar to the Lokpal, to handle impeachment cases could help ensure impartiality and reduce political interference.

- Allow MPs to Vote According to Conscience: Modifying the anti-defection law to allow MPs to vote based on their individual conscience, rather than following party directives, would ensure that impeachment motions are decided based on merit.