Presidential Reference Introduction

- Recently, the Supreme Court issued notices to the Union Government and all State Governments regarding a Presidential Reference seeking clarity on whether the judiciary can compel the President and Governors to act within specified timelines on bills passed by State legislatures. This case has attracted significant attention as it delves into the balance of power between constitutional authorities and the judiciary.

- A Constitution Bench, headed by Chief Justice B.R. Gavai, is slated to commence detailed hearings by mid-August, marking an important moment in the relationship between the judiciary and the executive, particularly concerning the timely assent of bills.

Background: The Constitutional Query

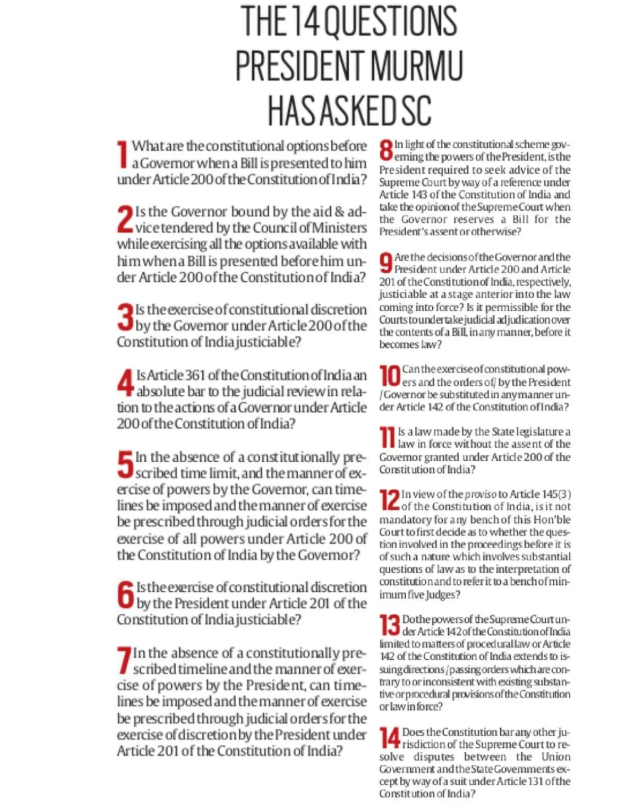

- The current Presidential Reference stems from Article 143 of the Indian Constitution, which allows the President to seek the Supreme Court’s opinion on significant constitutional questions. The reference follows President Droupadi Murmu’s submission of 14 questions to the Court, particularly regarding the April 2025 Supreme Court judgment.

- In this landmark ruling, the Court had examined a case brought by the Tamil Nadu government, where it was found that Governor R.N. Ravi had delayed assent to ten re-passed state bills. The Court deemed this delay illegal and imposed, for the first time, judicially enforceable timelines on both Governors and the President for the assent of bills.

- The present Reference seeks clarification on whether the judiciary has the authority to direct constitutional authorities like the President and Governors on how and when they should act on matters such as granting assent to State Bills. This brings into question the limits of judicial oversight and the separation of powers within India’s constitutional framework.

Key Aspects of the Issue

- Judicial Enforceability of Timelines: The crux of the case lies in whether the judicially imposed timelines for assent can be enforced by the courts, ensuring that Governors and Presidents comply with prescribed deadlines for bill assent.

- Article 143 of the Constitution: This constitutional provision allows the President to seek the Supreme Court’s opinion on constitutional matters. The current reference is a result of President Murmu’s decision to submit key queries following the Court’s April 2025 verdict.

- Governors’ Delay in Assent: The Supreme Court’s April 2025 ruling has set a precedent by scrutinizing the role of Governors in delaying assent to State Bills. This case specifically questioned Governor R.N. Ravi’s delay in assenting to Tamil Nadu’s bills, which led to the Court’s landmark judgment establishing enforceable timelines.

Scope and Significance of the Supreme Court’s Advisory Jurisdiction

- Constitutional Provision: Article 143(1) of the Indian Constitution empowers the President to refer legal or factual questions of significant public interest to the Supreme Court for its advisory opinion, even if there is no ongoing judicial proceeding.

- Historical Inspiration: This advisory jurisdiction draws from the provisions of the Government of India Act, 1935.

- Instances of Use: Since India’s independence, this provision has been invoked on at least 14 occasions.

- Limitations of Jurisdiction: The Supreme Court is confined to addressing only the specific legal or factual issues posed in the Presidential Reference and cannot expand its scope beyond the questions submitted.

- Debate in the Constituent Assembly: While the Constituent Assembly discussed concerns regarding potential political misuse of this power, the provision was ultimately retained to facilitate the resolution of constitutional uncertainties and deadlocks.

- Constitutional Safeguard: Article 145(3) stipulates that matters referred under Article 143 must be adjudicated by a Constitution Bench consisting of no fewer than five judges, ensuring careful and authoritative interpretation.

Supreme Court’s Discretion to Decline Presidential References

- Discretionary Nature of Article 143(1): Although Article 143(1) grants the President the authority to seek the Supreme Court’s opinion, the Court is not obligated to respond in every instance. The provision uses the word “may,” which indicates judicial discretion rather than compulsion.

- Special Courts Bill Case (1978): In this landmark case, the Supreme Court clarified that the term “may” in Article 143 provides the Court with the discretion to either answer or decline a Presidential Reference.

- Requirement to Provide Reasons: When the Court exercises its discretion to decline a Reference, it is required to record and explain its reasons for doing so.

- Dr. M. Ismail Faruqui v. Union of India (1994): The Court reaffirmed its position that References involving complex factual questions, expert evidence, or issues of a political nature may be declined in the interest of preserving judicial propriety.

- Refusal in Ayodhya Reference (1993): The Supreme Court declined to respond to the Presidential Reference concerning the Ayodhya-Babri Masjid dispute, citing the pendency of a related civil suit and concerns about constitutional impropriety.

- Jammu and Kashmir Resettlement Law Case (1982): The Court also declined to provide an opinion on a proposed law regarding migrant resettlement in Jammu and Kashmir because the legislation had already been enacted, rendering the Reference redundant.

- Judicial Caution and Integrity: These examples reflect the Supreme Court’s prudent use of discretion to avoid involvement in politically sensitive matters and uphold the independence and integrity of the judiciary.

Nature of Supreme Court’s Advisory Opinions

- Debate on Binding Nature: The question of whether advisory opinions given by the Supreme Court under Article 143(1) are binding remains a matter of legal debate and interpretation.

- Scope of Article 141: Article 141 states that only the “law declared” by the Supreme Court is binding on all courts in India. This has raised doubts about whether advisory opinions fall within its ambit.

- Clarification in St. Xavier’s College Case (1974): In this case, the Court explicitly clarified that advisory opinions issued under Article 143 do not constitute binding precedents but instead hold persuasive authority.

- Contrasting Approach in R.K. Garg Case (1981): Despite earlier assertions, the Supreme Court in R.K. Garg v. Union of India treated the reasoning of an advisory opinion as binding, reflecting an inconsistent stance on the matter.

- Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal Case (1991): The Court reiterated that advisory opinions deserve “due weight and respect,” yet stopped short of recognizing them as binding judicial decisions.

- Implication for Current Reference: Any opinion arising from the ongoing Presidential Reference will not override or dilute the binding nature of the April 2025 verdict, which was delivered through the Court’s adjudicatory jurisdiction.

- Influence on Future Cases: Although non-binding, the advisory opinion is expected to carry significant persuasive value and may shape the trajectory of ongoing and future litigations, especially those involving states like Kerala and Punjab.

Scope of Supreme Court’s Power to Modify April 2025 Verdict via Presidential Reference

- Limits of Article 143(1): The Supreme Court has consistently held that Article 143(1) cannot be invoked by the executive to seek a review or overturn an already adjudicated and final decision of the Court. This position was firmly established in the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal case.

- Finality of Judicial Decisions: Once the Supreme Court has pronounced a verdict under its adjudicatory jurisdiction, the judgment is deemed final. There is no scope for doubt or reconsideration that would warrant a Presidential Reference under Article 143(1).

- Permissible Avenues for Reconsideration: The only lawful and constitutional means to challenge or seek modification of a settled judicial verdict are through review petitions or curative petitions filed before the Supreme Court itself.

- Clarificatory Role Under Article 143(1): In the Natural Resources Allocation case (2012), the Court clarified that although it cannot alter the core decision through Article 143(1), it can clarify, interpret, or restate the legal principles involved, without affecting the parties’ rights or the essence of the original judgment.

- Precedent from the Collegium System (1998): In 1998, a Presidential Reference led to modifications in the functioning of the collegium system. However, the Court did not overturn the original 1993 decision but merely clarified certain aspects of its implementation.

- Current Context of April 2025 Verdict: While the April 2025 judgment remains binding and final, the current Presidential Reference may offer the Supreme Court an opportunity to clarify or elaborate on specific legal doctrines or reasoning used in the decision.

- Wider Constitutional Clarification: Given that the Reference contains 14 distinct questions—some of which extend beyond the scope of the April verdict—the Constitution Bench may use this occasion to provide broader constitutional interpretations without disturbing the original ruling.