Global Plastic Crisis Introduction

- Plastic pollution is escalating at an alarming rate, emerging as one of the most pressing global environmental challenges of our time.

- Its impacts extend far beyond the environment, affecting social wellbeing, economic stability, and human health, thereby posing a significant threat to the sustainable development agenda.

- Recognizing the urgent need for coordinated action, the United Nations has proposed a Global Plastic Treaty aimed at reducing plastic pollution worldwide.

What is the Global Plastic Pollution Treaty?

-

- In March 2022, during the UN Environmental Assembly (UNEA) in Nairobi, Kenya, 175 nations made a landmark decision: they voted in favor of establishing a global treaty to combat plastic pollution.

- This historic agreement set an ambitious target for implementation by 2025, signaling a collective commitment to tackling the crisis.

- The Plastic Pollution Treaty is a legally-binding international framework aimed at reducing plastic waste on both land and in oceans. Its primary goal is to:

- Minimize environmental and health impacts caused by plastic pollution.

- Encourage responsible production, consumption, and disposal of plastics.

- Strengthen international collaboration in monitoring, reporting, and addressing plastic waste.

- The Role of UNEP in Driving the Treaty: The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has been leading efforts to ensure countries reach a consensus on the treaty. UNEP facilitates negotiations, provides technical guidance, and helps align national policies with global sustainability objectives.

- Formation of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC): To draft and finalize the treaty, an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established.

Why the Global Plastic Pollution Treaty Matters?

- Scale of Plastic Pollution:

-

-

- 460+ million tons of plastic are produced annually worldwide.

- Only 9% of plastic is recycled; the rest contributes to waste accumulation.

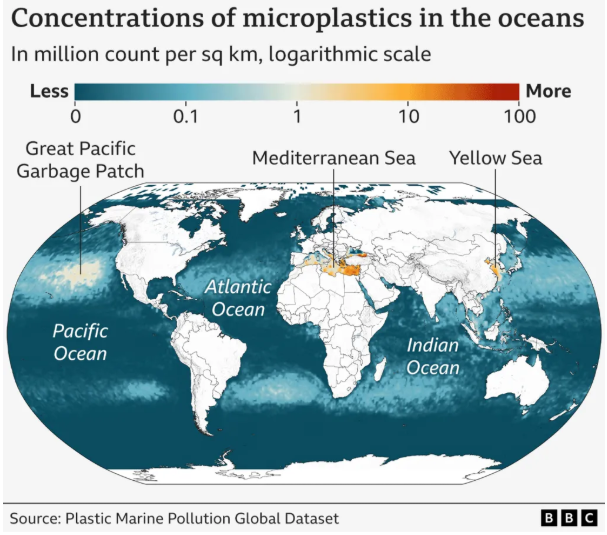

- Up to 14 million tons of plastic enter oceans each year.

- Plastic production may triple by 2060 without strong intervention.

-

- Environmental and Health Impacts:

-

-

- Drives biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation.

- Microplastics contaminate drinking water, food, and air globally.

- Tiny particles can carry hazardous chemicals, causing health risks such as endocrine disruption and toxicity.

-

- Economic Consequences:

-

-

- Plastic pollution costs billions of dollars annually, affecting fisheries, tourism, and cleanup efforts.

- Damages natural assets and increases public health expenditures, hindering sustainable development.

-

- Impact on Climate Change:

-

- Plastics are fossil fuel-based, and their lifecycle (production, use, disposal) emits significant greenhouse gases.

- The plastics sector currently contributes 3–5% of global emissions, projected to rise sharply with increasing demand.

Key Focus Areas of the Global Plastic Pollution Treaty

- Comprehensive Scope Across the Plastic Lifecycle:

-

-

- The treaty addresses all stages of plastics, including the design, production, use of hazardous chemicals, and waste management practices.

- By covering the entire lifecycle, the treaty ensures that plastic pollution is tackled in a holistic and integrated manner, rather than focusing only on end-of-life disposal.

-

- Legally Binding Measures:

-

-

- The treaty establishes mandatory commitments and binding targets for all participating countries.

- It focuses on phasing out high-risk single-use plastics, setting design requirements for sustainability, and creating compliance mechanisms to ensure enforcement.

- Unlike voluntary national initiatives, these measures are designed to ensure that countries are accountable for their actions.

-

- Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR):

-

-

- The treaty introduces extended producer responsibility, making manufacturers accountable for the lifecycle impacts of their plastic products.

- Producers are encouraged to adopt better product design and embrace circular economy principles.

- This ensures that the responsibility for plastic waste is shared by the producers, reducing environmental burdens on governments and society.

-

- Production Controls:

-

-

- The treaty addresses the upstream production of plastics, particularly the production of virgin or new plastics.

- Measures may include setting caps on production or requiring a minimum percentage of recycled content in new plastic products.

- These controls aim to limit the creation of new plastic, thereby reducing future pollution.

-

- Design for Reuse and Recycling:

-

-

- The treaty promotes the design of plastic products that are easier to reuse and recycle.

- It also encourages the elimination of problematic and unnecessary plastics that contribute to environmental harm.

- Improved product design ensures that plastics remain valuable resources rather than persistent pollutants.

-

- Enhanced Waste Management:

-

-

- The treaty emphasizes the improvement of waste collection and recycling infrastructure, especially in developing countries.

- Strengthening waste management systems ensures that plastics are effectively captured and recycled, minimizing leakage into oceans and land.

- Proper waste management supports sustainable development by protecting ecosystems and public health.

-

- Circular Economy Approach:

-

-

- The treaty promotes a circular economy, moving away from the traditional linear model of “take-make-dispose.”

- Plastics are kept in the economic loop for as long as possible, reducing environmental pollution and conserving resources.

- This approach ensures that plastic materials are reused, repurposed, and recycled instead of ending up in landfills or oceans.

-

- Regulation of Hazardous Chemicals:

-

- The treaty aims to regulate hazardous chemicals used in the production of plastics.

- Controlling toxic substances in plastics helps to protect human health and prevent environmental contamination.

- This ensures that plastic production is safer for both people and ecosystems

What are the Challenges in Negotiating the Global Plastic Pollution Treaty?

- Divergent Country Positions and Economic Interests:

-

-

- Since the start of negotiations, two broad coalitions have emerged: the High Ambition Coalition (HAC) led by Norway and Rwanda, which is highly organized and formal, and the Like-Minded Countries (LMC) group, which includes Iran, Saudi Arabia, China, and other major petrochemical-producing nations.

- Under current rules, no proposal can pass by a simple majority; near-unanimous agreement is required, giving each coalition significant leverage in shaping outcomes.

-

- Lifecycle vs. Waste Management:

-

-

- There is a fundamental divide over whether the treaty should cover the entire plastic lifecycle—from production and design to disposal and recycling—or focus only on waste management.

- HAC countries advocate for upstream controls, such as cutting or capping plastic production and polymer use.

- LMC countries argue that limiting production could disrupt trade and economic growth, emphasizing that effective waste management alone can mitigate pollution.

- India has aligned with the LMC viewpoint, stressing that negotiations should focus on plastic pollution rather than production, to avoid constraining the country’s developmental rights.

-

- Caps on Plastic Production:

-

-

- HAC countries support mandatory caps on primary plastic production, viewing them as essential to curb the rapid proliferation of plastics globally.

- In contrast, LMC countries oppose such caps, arguing that they could hinder economic development and innovation, particularly in petrochemical-dependent economies.

-

- Regulation of Chemicals of Concern:

-

-

- Negotiators remain divided on how to address hazardous chemicals present in plastics, including phthalates, BPA, and persistent organic pollutants.

- Disagreements focus on which chemicals should be banned or restricted and the mechanisms for updating these lists as scientific knowledge evolves.

- Resolving this issue is critical to protect human health and ecosystems from toxic plastic components.

-

- Financial and Technical Support for Developing Countries:

-

-

- Developing nations stress the need for fair and effective financial and technical assistance to implement treaty measures.

- Upgrading plastic waste infrastructure or transitioning to safer alternatives requires robust and accessible support, which remains a point of contention.

- Disputes persist over funding sources, financial mechanisms, and the responsibility of wealthier countries and producers to assist less developed nations.

-

- Pace and Progress of Negotiations:

-

- Independent observers have expressed concern about the slow pace of treaty discussions.

- For instance, Article 6 (Plastic Production) has yet to have a first reading, and Article 3 (Chemicals of Concern) continues to remain bracketed, reflecting unresolved disagreements.

- Without effective measures in these critical areas, the treaty risks failing to curb plastic pollution across its full lifecycle, potentially allowing continued plastic proliferation despite its adoption.

Way Forward

- Promote Parallel Progress in Negotiations:

-

-

- Negotiations on contentious articles, such as product standards, upstream controls, and the overall scope of the treaty, should proceed in parallel rather than being stalled by linked issues like finance or implementation.

- This approach can prevent stalemates, encourage all parties to remain actively engaged, and maintain momentum toward consensus.

-

- Adopt a Balanced Lifecycle Approach:

-

-

- The treaty should aim to address the entire lifecycle of plastics, including design, production, waste management, and hazardous chemicals.

- At the same time, it must recognize practical limitations, particularly for plastic manufacturers in developing countries, where strict caps on primary polymer production could hinder development in the absence of viable alternatives.

- Immediate attention should focus on eliminating the most harmful single-use plastics, while establishing pathways to expand regulatory measures to broader plastic categories over time.

-

- Blend Binding Commitments with Flexibility:

-

-

- Certain aspects of the treaty, such as the reduction of high-risk plastics and hazardous chemical use, should have binding obligations to ensure global accountability.

- Simultaneously, elements of the treaty can allow for voluntary or nationally determined measures to accommodate countries with unique economic or technological capacities.

- The treaty should include flexibility in implementation timelines and support mechanisms, allowing gradual adoption while maintaining environmental ambition.

-

- Ensure Adequate Financial and Technical Support:

-

-

- A credible treaty must establish clear and accessible funding mechanisms to help countries meet their obligations, particularly developing nations facing disproportionate burdens.

- Support mechanisms could extend beyond the Global Environment Facility, encompassing financial and technical assistance for infrastructure development, capacity building, and safer alternatives to plastics.

-

- Recognize and Include Local and Subnational Voices:

-

- Local and subnational governments, which are responsible for waste management, public education, and land-use planning, should be explicitly acknowledged in the treaty’s legal text and financial arrangements.

- Inclusion of these actors ensures that policy implementation is practical, context-specific, and more effective, bridging global commitments with on-the-ground action.