Global Hunger Index Introduction

- The Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2024, published by Concern Worldwide (Ireland) and Welt Hunger Hilfe (Germany), ranks India at 105th out of 127 countries.

- While there is a slight improvement from India’s 111th position in 2023, the report raises critical concerns regarding hunger and malnutrition, despite India being one of the largest food producers in the world with an impressive output of 332 million tonnes in 2023-24.

- The ongoing disparity between food production and malnutrition indicates deep-rooted issues in India’s healthcare systems, social welfare policies, and nutritional access.

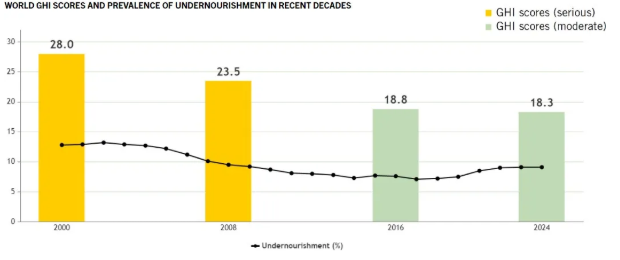

Global Hunger: Lack of Progress

- The GHI 2024 report points to a worrying trend on a global scale, showing that 42 countries are currently experiencing “serious” or “alarming” levels of hunger, with little to no progress in recent years.

- It is predicted that 64 countries may miss the 2030 Zero Hunger target, with global hunger eradication potentially delayed until 2160.

- The stagnation in hunger reduction is attributed to factors like climate change, the Russia-Ukraine war, the Israel-Palestine conflict, and the ongoing economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. These have disrupted food systems, supply chains, and aid distribution across the globe.

Hardest-hit Regions

- The region most affected by hunger is Africa South of the Sahara, where hunger levels are exacerbated by persistent conflicts, economic challenges, and high child mortality rates.

- Since 2016, progress in hunger reduction in this region has been minimal, signaling an urgent need for more sustainable interventions.

India’s GHI 2024 Performance: Key Indicators

- Rank: 105 out of 127 countries

- GHI Score: 27.3 (on a scale where 0 is best, and 100 is worst)

- Hunger Status: Serious

- Undernourishment Rate: 13.7%

- Child Wasting: 18.7% (children with low weight for height)

- Child Stunting: 35.5% (children with low height for age)

- Child Mortality: 2.9% (deaths of children under five)

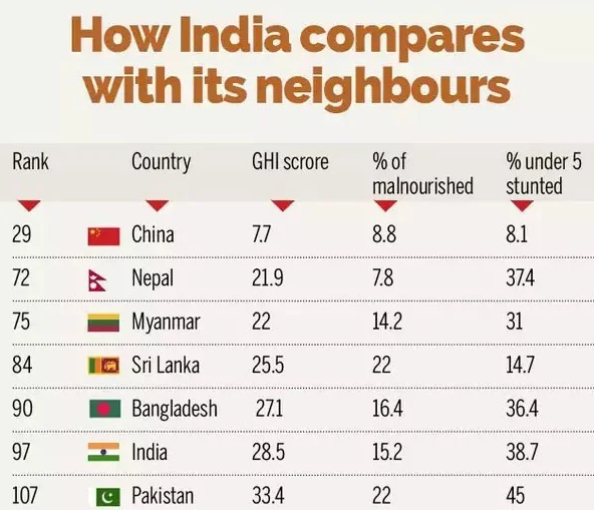

India vs. South Asia

- India’s performance contrasts with neighboring countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, which have achieved better rankings and fall into the “moderate” hunger category, indicating relatively better outcomes in terms of nutrition.

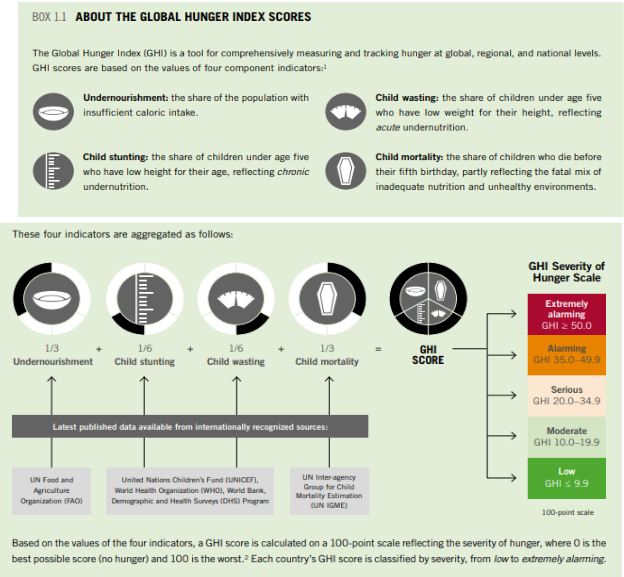

Global Hunger Index

- The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a composite tool that measures hunger across different dimensions. The GHI score for each country is derived from four key indicators:

- Undernourishment: Proportion of the population that lacks sufficient caloric intake.

- Child Stunting: Percentage of children under five years who have low height for their age, indicating chronic malnutrition.

- Child Wasting: Percentage of children under five with low weight for their height, a sign of acute malnutrition.

- Child Mortality: Percentage of children who die before their fifth birthday, reflecting the severe impact of malnutrition and poor living conditions.

Indian Government’s Critique of GHI Methodology

- Child-Centric Indicators: The GHI relies heavily on child-related indicators (child stunting, child wasting, and child mortality), which the government argues do not represent the overall hunger status of the entire population.

- Undernourishment Data: The undernourishment indicator is based on a limited survey of only 3,000 respondents, which the government claims is not a representative sample for a nation of over a billion people.

- Child Mortality as a Hunger Indicator: The government has questioned the direct correlation between child mortality and hunger, arguing that several other factors, such as healthcare infrastructure and disease, influence child mortality rates.

- Data Discrepancies: The GHI reported a child wasting rate of 18.7%, which conflicts with the Poshan Tracker data, where India recorded a child wasting rate of 7.2%, highlighting inconsistencies between international reports and national statistics.

Why Hunger Persists in India?

Despite the Indian government’s criticism of the Global Hunger Index (GHI), data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) continues to highlight widespread malnutrition. Several key challenges contribute to India’s ongoing hunger crisis:

- Low Productivity from Small Holdings: Approximately 50 million households in India rely on small and marginal landholdings for their livelihoods. These small farms face numerous challenges, including soil degradation, which reduces fertility and crop yield, and fragmented landholdings that make efficient farming difficult.

- For instance, states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, where the average landholding is under 1 hectare, report lower agricultural productivity, exacerbating food insecurity.

- Moreover, fluctuating market prices for agricultural products leave small farmers vulnerable, as seen during the onion price crash of 2020, which severely affected incomes in regions like Maharashtra.

- Rural Unemployment and Low Income: The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017-18 revealed that rural unemployment was at 6.1%, the highest since 1972-73. With unemployment rising and rural wages stagnating, many families face reduced purchasing power, making it difficult to afford adequate food.

- For instance, agricultural laborers in Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh face erratic employment due to seasonal agriculture, which limits their ability to buy nutritious food.

- A study from Oxfam India found that rural households spend over 60% of their income on food, leaving little room for savings or nutritional diversity.

- Public Distribution System (PDS) Inefficiencies: The PDS, designed to provide subsidized food grains to low-income households, suffers from corruption, inclusion errors, and technical glitches.

- Many of these issues stem from the complex Aadhaar-linked biometric verification system, which often fails in remote areas due to poor connectivity, preventing eligible beneficiaries from accessing their entitlements.

- A report by PRS Legislative Research highlighted that nearly 12% of rural beneficiaries in Bihar and Odisha are excluded from PDS due to these glitches.

- Additionally, ghost beneficiaries and diversion of PDS grains to the open market in states like West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh further reduce the efficiency of the system, leaving the most vulnerable without adequate food supplies.

- Protein Deficiency: Pulses, a major source of protein, are crucial to addressing protein hunger in India, yet they are often inadequately included in the PDS due to budgetary constraints.

- For instance, while pulses are a key component of the diet in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, these states have struggled to distribute them effectively through PDS.

- Additionally, many states, such as Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, exclude eggs from their mid-day meal programs, depriving children of a vital source of protein.

- Research from the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) has shown that children in states that include eggs in mid-day meals, such as Tamil Nadu and Odisha, have better nutritional outcomes compared to those that do not.

- Micronutrient Deficiency (Hidden Hunger): Often referred to as hidden hunger, micronutrient deficiency is rampant in India, particularly among pregnant and lactating women and young children.

- The National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB) found that nearly 50% of pregnant women in rural India suffer from anemia, caused by iron deficiency.

- This is exacerbated by inadequate dietary diversity and a reliance on staple grains like rice and wheat, which do not provide essential micronutrients like vitamin A, iodine, and zinc.

- Additionally, a UNICEF report noted that 40% of Indian children under the age of five are vitamin A deficient, increasing their risk of blindness and susceptibility to infections.

- The absence of fortified foods and poor access to supplements, especially in backward regions like Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, continue to perpetuate this hidden hunger.

Government Measures to Combat Hunger

- National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013: This law continues to be a cornerstone of India’s fight against hunger, ensuring that 75% of rural and 50% of urban populations receive subsidized food grains through the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS). Under this act, eligible families receive 5 kg of food grains per person per month at highly subsidized rates.

- POSHAN Abhiyan (National Nutrition Mission): The initiative uses a multi-sectoral approach to improve nutritional outcomes by promoting convergence among various ministries, leveraging real-time monitoring through the POSHAN Tracker, and ensuring community-based interventions.

- Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY): Launched during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, PMGKAY provided free food grains (5 kg per person per month) to over 800 million beneficiaries under the NFSA.

- Mission Poshan 2.0: This program, introduced in the Union Budget 2021-22, is an enhanced version of the POSHAN Abhiyan and integrates the Supplementary Nutrition Programme with the Anganwadi Services under ICDS (Integrated Child Development Services). The mission emphasizes the need for nutrition-smart villages and seeks to diversify diets by incorporating locally sourced, nutrient-rich foods into Anganwadi meals.

- Food Fortification: Programs like the Fortification of Rice and Distribution through the PDS were expanded in 2021, targeting over 112 million children and pregnant and lactating women in mid-day meals, Anganwadi schemes, and PDS. This includes fortifying staples such as rice, milk, salt, and edible oil with essential nutrients like iron, folic acid, iodine, and vitamins A and D.

- Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY): This maternity benefit scheme offers a cash incentive of ₹5000 in three installments for the first live birth, helping to bridge gaps in nutrition during a critical period. It also addresses nutrition gaps in rural and tribal regions where maternal malnutrition remains a significant issue.

- Eat Right India Movement: Spearheaded by FSSAI (Food Safety and Standards Authority of India), the Eat Right India Movement has been gaining momentum. This program aims to educate citizens about healthy eating habits and food safety. This campaign also promoted International Year of Millets 2023.

- One Nation, One Ration Card (ONORC): Launched in 2020, ONORC aims to streamline access to the PDS across the country by allowing beneficiaries to access subsidized food grains from any fair price shop (FPS) across India, regardless of their home state. By 2024, ONORC has been implemented across all states and Union Territories, enabling nearly 240 million beneficiaries to seamlessly access food grains.

- Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0: This recent initiative, introduced in 2021, consolidates various schemes under Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) to strengthen Anganwadi infrastructure and nutritional services. The program focuses on the first 1,000 days of a child’s life, recognized as the most critical period for growth and development.

Way Forward

- Boosting Agricultural Productivity for Small and Marginal Farmers: Small and marginal farmers form the backbone of India’s agriculture sector, and the government and other stakeholders need to provide support in the form of subsidized seeds, organic fertilizers, and access to modern irrigation techniques.

- For example, Andhra Pradesh’s Zero-Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) initiative has shown promise in improving productivity for small farmers by encouraging the use of natural inputs like manure and crop rotation, reducing their dependence on costly chemical fertilizers.

- Similarly, the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana (PMKSY) promotes micro-irrigation systems, which has helped increase crop yields in drought-prone regions like Maharashtra and Gujarat by improving water-use efficiency.

- The recent implementation of e-NAM (National Agriculture Market) is a positive step, helping farmers in states like Karnataka and Haryana gain access to wider markets and better prices for their produce.

- Nutritional Supplements in Mid-Day Meals: In states like Tamil Nadu, Odisha, and Telangana, where eggs are included in mid-day meals, studies have shown a significant reduction in malnutrition and anemia rates. Conversely, states like Gujarat, which exclude eggs from mid-day meals, continue to face challenges in improving child nutrition outcomes. The inclusion of eggs or pulses can provide much-needed protein, while adding fortified rice and wheat can address hidden hunger caused by micronutrient deficiencies like iron and vitamin A deficiency.

- For example, Karnataka has piloted a program where local millets are included in the mid-day meals, which has enhanced nutrition while promoting the use of indigenous crops.

- Strengthening Rural Employment Schemes: Expanding MGNREGA to offer more workdays, particularly during the lean agricultural season, can help boost incomes in areas with high food insecurity.

- For instance, in Rajasthan, MGNREGA has been instrumental in providing employment during drought periods, ensuring rural families have the purchasing power to buy food.

- Additionally, states like Kerala have creatively linked MGNREGA with agricultural activities, encouraging work on soil health improvement and community farming projects, which not only generate employment but also improve local food production.

- Improving Public Distribution System (PDS) Efficiency: The Public Distribution System (PDS) plays a key role in ensuring access to food grains for millions of low-income households. However, inefficiencies, such as leakages, inclusion errors, and Aadhaar-related technical glitches, prevent many from benefiting. To improve PDS efficiency, the government must streamline Aadhaar-linked biometric verification, and fix delivery chain issues.

- For example, states like Chhattisgarh have significantly reduced PDS corruption by implementing real-time monitoring systems and end-to-end computerization.

- In Madhya Pradesh, reforms in the PDS, such as the inclusion of fortified rice in the ration distribution, have helped combat hidden hunger by ensuring the distribution of nutritionally