Death Penalty in India Introduction

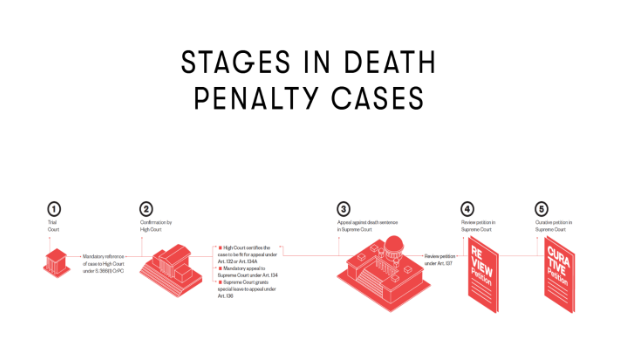

- The Supreme Court has clarified that it retains the power to reconsider its own judgment awarding the death penalty if it finds that the sentencing was imposed without following the guidelines previously laid down by the court.

- In a recent decision, the court set aside the death penalty awarded to a man convicted of the rape and murder of a four-year-old child. It observed that under Article 32 of the Constitution, the apex court is empowered to reopen the sentencing stage in cases involving capital punishment.

- The case relates to Vasanta Sampat Dupare, whose death sentence for the rape and murder of a four-year-old was upheld by the Supreme Court in 2017. However, the court has now ordered a fresh hearing on the quantum of his punishment.

- It must be noted that The Law Commission of India, in its 2015 report, recommended abolishing the death penalty for all offences except terrorism-related crimes and those involving waging war against the nation. However, India remains among the 55 countries that still retain the death penalty for ordinary crimes, as highlighted by Amnesty International’s 2023 data.

Key Legal Developments in India’s Death Penalty Sentencing Framework

-

- The “Rarest of Rare” Doctrine: The foundation of India’s death penalty jurisprudence was laid in the Bachan Singh case (1980). The Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of capital punishment but ruled it must only be imposed in the “rarest of rare” cases. Importantly, the Court mandated that judges must consider not only the gravity of the crime but also the individual circumstances, social background, and potential for reform of the accused.

- Procedural Lapses as Constitutional Violations: In Bariyar (2009), Justice S.B. Sinha emphasized that failures in following sentencing procedures are not just judicial oversights but amount to constitutional violations. This recognition elevated the process of sentencing itself to a matter of fundamental rights, reinforcing the requirement for reasoned, individualized consideration before awarding capital punishment.

- Structured Sentencing Framework: The Manoj guidelines (2022) introduced by a three-judge bench revolutionized sentencing hearings. The Court made it mandatory for trial courts to obtain:

-

- Probation officer reports on the socio-economic background of the accused

- Psychiatric and psychological evaluations

- Prison conduct records

- This ensured that sentencing decisions were based on holistic evidence about the convict’s life circumstances and mental health, rather than just the crime’s brutality.

- Enforcing Compliance with Manoj Guidelines: Until recently, the Manoj framework was often ignored, as non-compliance carried no legal repercussions. In Dupare (2025), the Supreme Court made it clear that failure to follow the Manoj guidelines would invalidate sentencing proceedings. This marked a turning point by attaching consequences to procedural violations, making rights-based sentencing enforceable in practice.

- Anchoring Death Sentencing under Article 21:Collectively, these cases have transformed death penalty jurisprudence by rooting it firmly within the constitutional guarantees of equality, dignity, and due process under Article 21. Sentencing can no longer rely solely on judicial discretion—it must be procedurally robust and evidence-driven.

- Proactive Judicial Responsibility: Another crucial development is the Court’s insistence that judges must actively seek information about the accused, particularly for the poor and marginalized who lack resources to present mitigating evidence. This proactive duty transforms sentencing from a passive evaluation to a judicially guided rights-protection exercise.

Issues in India’s Death Penalty Sentencing Procedures

- Crime-Focused, Not Accused-Focused Approach: Despite repeated Supreme Court directions—from Bachan Singh (1980) to Manoj (2022)—trial courts and even higher courts often reduce sentencing to a crime-centric exercise. Judges rely heavily on the brutality of the offence, sidelining the accused’s life history, mental health, and capacity for reform that must constitutionally influence the sentencing decision.

- It must be noted that as compared to 13 offences in Indian Penal Code (IPC), the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) has now 15 offences punishable with death penalty.

- Disproportionate Impact on the Marginalized: Empirical data shows that the death penalty in India is overwhelmingly imposed on economically disadvantaged and socially marginalized groups. Defendants from Dalit, Adivasi, and OBC communities, or those lacking access to quality legal representation, are the most vulnerable. Their inability to present mitigating evidence such as family history, trauma, or poverty-driven circumstances compounds systemic inequities.

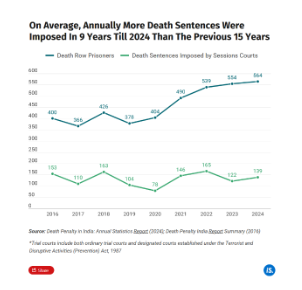

- Alarming Violation Rates: A recent study by the Project 39A, Square Circle Clinic (2023) highlights that 94% of trial court death sentences after 2022 have violated the Manoj guidelines. Courts continue to focus disproportionately on the gruesomeness of the crime while neglecting the legally required consideration of the accused’s socio-economic background, psychological profile, and mitigating circumstances. UP’s sessions courts imposed 34 death sentences in 2024, the most in the country and higher than the state’s average since 2016.

- Four Decades of Non-Compliance: For over 40 years since the Bachan Singh ruling, courts have routinely ignored sentencing safeguards. The absence of an institutionalised monitoring mechanism has allowed procedural violations to persist unchecked, making sentencing arbitrary and inconsistent with constitutional guarantees. Gathering information on the prisoners for trial courts, through social workers or mental health professions, is limited due to a staff shortage, and they have to rely on reports prepared by a probation officer and a jail superintendent.

- The Information Gap in Defense Representation: Poor and under-resourced defendants often cannot furnish detailed life-history information required for mitigating arguments. Without proactive judicial intervention and state-supported mechanisms (such as probation reports or psychiatric evaluations), courts fail to access vital insights into the convict’s background. This gap leaves the accused without a fair chance at presenting mitigating factors that could alter the sentence.

- The Project 39A report showed that death sentences were imposed on the same day, or within one day of conviction, in nearly a third of death penalty cases at the trial courts in 2024.

- Also, the cash bail scheme that the union government initiated in 2023 to support poor prisoners has not been effectively utilised and implemented by states.

Way Forward

- Recognition of Fundamental Rights Violations: The Court ruled that non-compliance with sentencing protocols, including those set out in the Manoj guidelines (2022), is not merely a procedural lapse but a direct violation of Article 21. This recognition means the right to life cannot be curtailed unless strict constitutional safeguards are met.

-

- Mandatory Setting Aside of Unlawful Sentences: The judgment creates a binding precedent: any death sentence imposed in violation of Manoj protocols must be set aside. This includes cases where trial courts failed to consider mitigating circumstances, probation reports, psychiatric assessments, or prison conduct records before deciding on capital punishment.

- Retrospective Application of Safeguards: Importantly, the Court extended protections to prisoners sentenced before 2022, allowing them to demand fresh sentencing hearings. This retrospective application ensures that long-standing procedural deficiencies do not deprive death row prisoners of their constitutional rights.

- Widespread Impact Across Death Row Population: India currently houses nearly 600 prisoners on death row, many of whom were sentenced without compliance to mandated safeguards. The Dupare ruling potentially opens the door for hundreds of rehearings nationwide, making it one of the most consequential death penalty decisions since Bachan Singh (1980).

- From Guidance to Constitutional Guarantee: Earlier, the Manoj guidelines were treated as judicial recommendations, often disregarded in lower courts. With Dupare, they have been transformed into strict constitutional obligations. Judges must now actively investigate the life circumstances of the accused rather than relying solely on the crime’s brutality.