Uranium Mining In Meghalaya

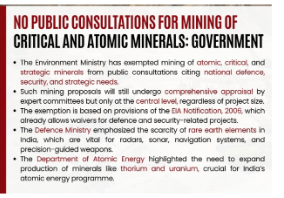

- Recently, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change issued a memorandum exempting the mining of atomic minerals, including uranium, from the process of public consultation.

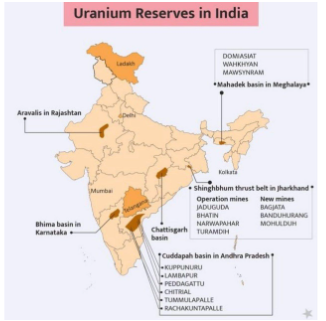

- This decision has sparked concern among tribal communities in Meghalaya, which possesses some of India’s largest uranium reserves.

- India contributes around 1% of global uranium production and was ranked as the ninth-largest uranium producer in 2023, with a 0.32% increase in output compared to 2022.

- From 2017 to 2022, India’s uranium production grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9%, and it is projected to continue increasing at a CAGR of 6% between 2023 and 2027 .However, uranium mining poses significant environmental and public health risks due to its radioactive nature.

History of Uranium Mining Resistance in Meghalaya

- Khasi Opposition Since the 1980s: Communities in Domiasiat and Wahkaji have resisted uranium exploration and mining for over four decades.

- Lessons from Jharkhand: The experience of Singhbhum mines, where protests erupted over radiation exposure, health hazards, and loss of livelihoods, has deepened mistrust among Meghalaya’s tribal groups.

- Procedural Unfairness: Public hearings have often been conducted in unfamiliar languages, effectively silencing local voices and ignoring community objections.

Why is the New Office Memorandum Problematic?

-

- Exempts Public Consultation: The OM removes the requirement for affected communities to be consulted before uranium mining begins, silencing indigenous participation.

- Issued Without Parliamentary Oversight: As an executive instrument, the order bypasses legislative debate and independent scrutiny, raising questions of executive overreach.

- Erodes Constitutional Safeguards: By ignoring participatory frameworks, the memorandum reduces tribal landholders to mere bystanders in decisions that affect their survival.

Which Constitutional and Legal Safeguards are at Stake?

- Sixth Schedule: Grants significant autonomy to the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council, which may be invoked to resist uranium mining projects.

- Judicial Precedents: In the Niyamgiri judgment (2013), the Supreme Court recognized the primacy of tribal consent in resource projects, setting a vital precedent.

- Fifth and Sixth Schedules: Provide a robust legal framework for protecting tribal rights and self-governance in scheduled areas.

- Global Principle of FPIC: The Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) principle, central to international indigenous rights law, has been disregarded in this decision.

Key Issues with Uranium Mining in India’s Tribal Regions

-

- Forced Extraction and Ignored Consent: The government has often pursued uranium mining projects without meaningful community participation. For example, in Meghalaya, the Centre decided to push ahead with uranium extraction despite repeated resistance, effectively sidelining the principle of free, prior, and informed consent of tribal communities.

- Language and Accessibility Barriers: Tribal resistance is compounded by the lack of accessible communication. In Jharkhand’s Singhbhum district, the Uranium Corporation of India Limited (UCIL) issued official notices in languages unfamiliar to the local population, effectively excluding them from voicing objections or participating in the decision-making process.

- Resource Frontier Perception and Marginalisation: For many tribal communities, uranium mining reinforces the perception of their land as a “resource frontier” for the rest of India, fueling narratives of exploitation, displacement, and cultural marginalisation. This deepens historical grievances of indigenous groups already struggling with loss of autonomy and ecological degradation.

Environmental and Social Impacts of Uranium Mining on Local Communities

- Ecological Pollution and Irreversible Damage: Uranium extraction is highly polluting by nature, leaving behind toxic waste that contaminates air, water, and soil. Once mining begins, the landscape undergoes permanent alteration—ecosystems are disrupted, water bodies are polluted, and biodiversity is lost. Such environmental damage is irreversible, undermining the long-term sustainability of fragile ecosystems.

-

- Radiation Exposure and Health Risks: Communities near uranium mines face the constant risk of radiation exposure. Evidence from Singhbhum in Jharkhand shows villagers suffering from higher incidences of cancer, genetic mutations, and chronic respiratory diseases. Radiation further contaminates agricultural land and groundwater, amplifying the public health crisis. It has been reported that the prevalence of respiratory diseases in communities affected by uranium mining is 1.3 times greater than that in non-affected communities.

- Constitutional and Legal Violations: Proceeding with uranium mining in tribal areas without free, prior, and informed consent directly undermines protections under the Fifth and Sixth Schedules of the Indian Constitution. These provisions were specifically designed to safeguard tribal autonomy, customary practices, and land rights, yet executive orders bypassing public hearings weaken these constitutional guarantees.

- Alteration of Landscape and Cultural Practices: Mining activities result in deforestation, loss of fertile land, and altered water systems, which devastate the traditional lifestyles of tribal communities. These areas are not only economic resources but also carry cultural and spiritual significance. Disruption of landscapes erodes cultural identity, social structures, and the intergenerational connection with land.

- Health Hazards Beyond Radiation: Beyond radiation, uranium mining releases heavy metals and chemical byproducts into the environment, contaminating drinking water and soils. For instance, the use of a radioactive component has exacerbated the complexities and dispersal of diseases, primarily due to the lack of waste disposal, which has caused kidney damage and genetic damage, i.e., dwarfism, infertility, etc. in people of Jadugoda in Jharkhand.

- Data shows that 9.25% of mothers in this area give birth to children with congenital deformities, often leading to infanticide.

-

- As per a study, Jharkhand’s average life expectancy is 62 years, 68% of individuals in Jadugoda die before reaching that age.

- Loss of Livelihoods and Economic Displacement: Agriculture, forestry, and animal husbandry—the traditional sources of livelihood for tribal communities—become unsustainable due to soil degradation, water scarcity, and land acquisition for mining projects. This loss forces migration, unemployment, and social dislocation, creating cycles of poverty and dependency.

Way Forward

- Judicial Interventions and Court Challenges: Affected communities can approach the judiciary to challenge the legality of the Office Memorandum (OM) exempting uranium mining from public consultations. The Supreme Court’s Niyamgiri Judgment (2013), which upheld the primacy of Gram Sabha consent for resource projects, provides a strong precedent for protecting tribal land and cultural rights. Judicial scrutiny can restore democratic oversight and ensure compliance with constitutional safeguards.

-

- Constitutional Protections under Fifth and Sixth Schedules: The Constitution grants special protections for tribal regions under the Fifth and Sixth Schedules. In Meghalaya, the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council (KHADC) has powers of local governance that can be invoked to resist unilateral mining projects. These provisions reinforce tribal self-determination, making it imperative that mining decisions respect local governance institutions rather than bypassing them.

- Adherence to Global Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) Norms: International norms, particularly the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), emphasize Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) before initiating resource extraction projects. Incorporating FPIC into Indian policy would ensure that tribal communities are active decision-makers, not passive bystanders, in determining the future of their land and resources.

- Alternative Strategies for Resource Security: Instead of forcing extraction in resistant tribal areas, the government can explore:

-

-

- Other uranium-rich regions such as Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan with fewer social conflicts.

- Substitute technologies in nuclear energy, such as thorium-based reactors, leveraging India’s significant thorium reserves.

- Diversified power generation using renewables like solar and wind, reducing dependence on uranium altogether.

- Such alternatives can meet India’s energy needs without ignoring democratic consent and ecological risks.

- Withdrawal of Controversial Executive Orders: The Environment Ministry must withdraw the contentious Office Memorandum that exempts mining of atomic and strategic minerals from mandatory public consultations. This policy sets a dangerous precedent by eroding participatory democracy and weakening environmental clearances. A withdrawal would reaffirm the government’s commitment to constitutional governance.

-

- Dialogue and Participatory Governance Approach: Coercive methods risk long-term alienation and unrest. Instead, the Centre should engage in transparent dialogue with tribal councils, community leaders, and civil society groups. Participatory governance not only addresses community concerns but also builds trust in state institutions, ensuring that development projects are inclusive and sustainable.