Caste Census India Introduction

- The Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) has approved the inclusion of caste data in the upcoming population census. The 2021 Census, originally scheduled to take place, has been postponed indefinitely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- This decision has reignited the ongoing debate regarding the role of caste-based enumeration in governance, policymaking, and political discourse in India.

What is the Census?

- The Census is a regular and organized process of collecting demographic, economic, and social information about a population within a designated area.

- Governments typically carry out the Census to obtain comprehensive data on the population’s characteristics and living conditions.

- This vital information helps governments, businesses, researchers, and policymakers plan public services, allocate resources, and make data-driven decisions for effective governance.

Overview of Census in India

- Purpose and Importance of Population Census:

- The population census provides vital statistics regarding human resources, demographics, culture, and the economic structure across all administrative levels in India.

- The first census in India was initiated in 1872 as a non-synchronous census, with the first synchronous census taking place in 1881 under British rule, conducted by W.C. Plowden.

- The census is conducted every 10 years by the Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner under the Ministry of Home Affairs.

- Legal and Constitutional Basis:

- The census is classified as a Union subject under Entry 69 of the Union List in the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

- It is governed by the Census Act of 1948.

History and Status of Caste Census in India

- Caste Data Collection in British India:

- During British rule, caste data was collected from 1881 to 1931 as part of the Indian census.

- After 1951, caste enumeration was discontinued, except for the data on Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

- Efforts Post-Independence:

- In 1961, the Indian government recommended that individual states carry out their own surveys on Other Backward Classes (OBCs), as central OBC reservations did not exist at the time.

- While the census remains a central subject, the Collection of Statistics Act, 2008, allowed states and local bodies to collect data, which led to states like Karnataka (2015) and Bihar (2023) conducting their own caste surveys.

Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC)

- The last national effort to collect caste data was made during the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC), which aimed to assess the socio-economic conditions of households, including caste information.

- The Ministry of Rural Development conducted the rural survey.

- The Ministry of Housing & Urban Poverty Alleviation managed the urban survey.

- The socio-economic data was published in 2016, but caste data was withheld.

- The raw caste data was transferred to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, which formed an Expert Group led by Arvind Panagariya to classify the data.

- It remains unclear whether the Expert Group’s report was submitted, as no public report was released.

- Learnings from the SECC (2011):

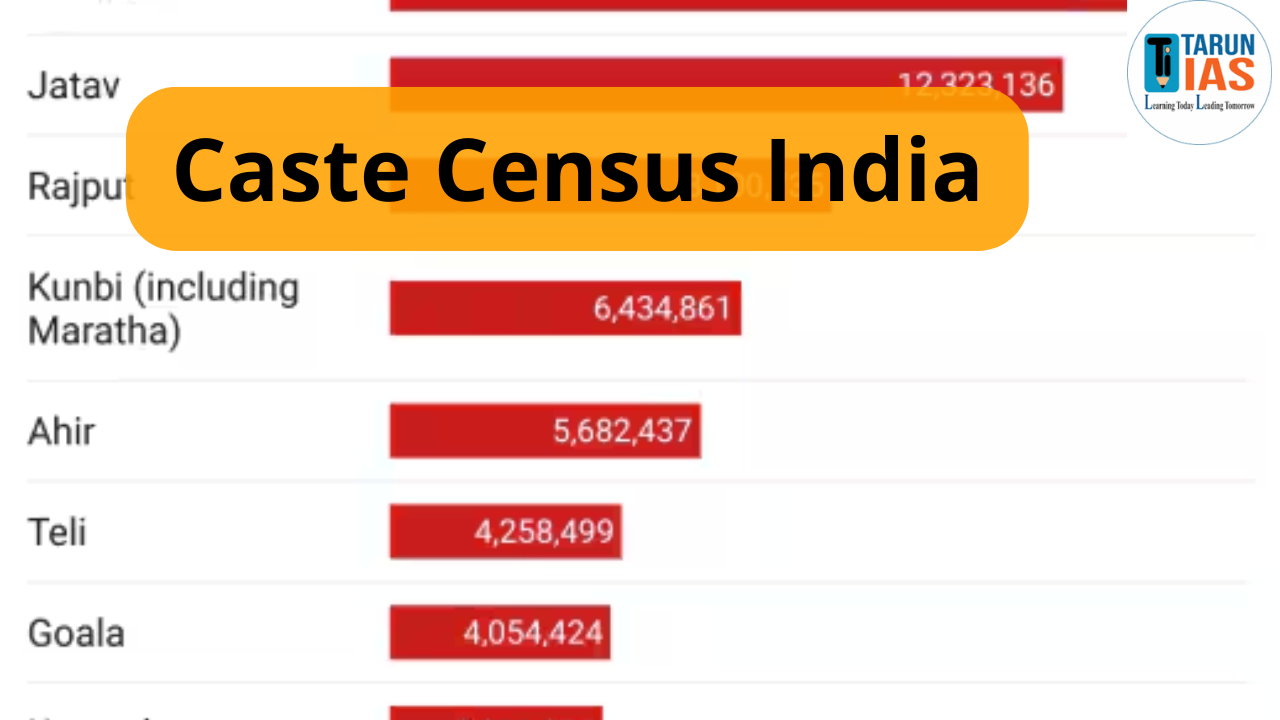

- The SECC recorded 46 lakh caste names due to its open-ended format, which was far higher than the 4,147 castes recorded in 1931.

- This led to data inflation, as people often entered sub-caste names or surnames (such as Gupta, Agarwal).

- To avoid this issue, a standardized code directory will be used in the upcoming census.

Key Highlights of the Caste Census Decision

- Digital Mode & Caste Directory:

- For the first time, the Census will be conducted in digital mode, utilizing a mobile app.

- A new “Other” column, along with a drop-down caste code directory, will be included alongside the SC/ST column.

- The software for this new system is currently undergoing testing to ensure smooth implementation.

- Development and Testing of Caste Code Directory:

- The Central OBC list, which includes 2,650 communities, along with the SC list (1,170) and ST list (890), will be merged with State OBC lists to form a comprehensive caste codebook.

- A pre-test will be conducted to address any potential issues before the official enumeration.

- Major Policy Shift After Decades:

- The CCPA’s approval to include caste data in the upcoming census marks the first comprehensive caste enumeration since 1931, excluding the data on SCs and STs.

- Historical Context of Caste Enumeration:

- Post-Independence censuses (1951-2011) excluded caste data collection, except for SC/ST figures.

- The last complete caste census was conducted in 1931, with caste data from 1941 remaining unpublished.

- Reliance on Estimates:

- In the absence of official data, estimates, such as the Mandal Commission’s estimate that 52% of the population belongs to OBCs, have guided policy and electoral decisions.

- Bureaucratic and Data Classification Challenges:

- Accurate caste data collection is hindered by overlapping caste names, classification ambiguities, and lack of clarity regarding inter-caste or migrant identities.

- Inconsistent State-Level OBC Lists:

- Different states maintain varying OBC lists and sub-categories like Most Backward Classes, which complicates efforts to create a unified national caste database.

- Renewed Debate on Governance and Representation:

- The decision to include caste data revives the broader debate on how such data should influence governance, social justice, and political representation in India.

What is the Procedure?

- Training of Government Officials:

- Approximately 30 lakh government officials will need retraining to implement the new digital format effectively.

- Census Phases: The census will be conducted in two phases:

- Phase 1: House listing and housing schedule, which includes 31 questions and has already been notified in 2020.

- Phase 2: Population enumeration, which includes 28 questions. It was tested in 2019 but has yet to be officially notified.

Significance for Delimitation & Women’s Reservation

- The new census findings will be used for:

- Redrawing Lok Sabha constituencies (delimitation).

- Implementing 33% women’s reservation in Parliament and State Assemblies.

Arguments in Favor of the Caste-Based Census

- Accurate Data for Targeted Welfare: A caste-based census allows for precise identification of socio-economic conditions across various caste groups, enabling the government to allocate resources more effectively. For example, the Mandal Commission’s recommendations in the 1990s were based on an estimation of 52% of the population being from the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). With accurate census data, welfare programs can be better tailored to meet the needs of these communities.

- Identification of Disparities: The caste-based census can highlight existing gaps in key sectors such as education, employment, and healthcare. For instance, research shows that OBCs, Dalits, and Tribals often have lower literacy rates and higher unemployment rates compared to other groups. Accurate data can ensure that resources are directed to areas where inequality is most pronounced, thereby addressing regional and sectoral imbalances.

- Strengthening Affirmative Action: Updated caste data can improve the effectiveness of affirmative action policies. A prime example is the reservation system in India, which has been criticized for being outdated. A comprehensive caste-based census could provide more accurate numbers, ensuring that affirmative action policies are more responsive to the needs of marginalized communities. For instance, the implementation of reservations could be adjusted based on real-time data to ensure better opportunities for underrepresented groups in education and employment.

- Social Justice: A caste-based census could act as a catalyst for social justice by influencing the development of policies that aim to uplift historically disadvantaged communities. A clear example of this is the demand for increased representation of OBCs and Dalits in higher education and public services. Having accurate caste data would ensure that the benefits of social justice policies reach those who truly need them, minimizing disparities.

- Policy Evaluation and Reform: The caste-based census provides a solid foundation for evaluating the impact of current social policies. For example, the lack of caste-based data has led to the reliance on estimates for policymaking. With accurate data, the government can evaluate how policies like reservations, scholarships, and job quotas have impacted various caste groups. This could lead to targeted policy reforms and improved governance, ensuring that the measures are both equitable and effective.

Arguments Against the Caste-Based Census

- Perpetuation of Caste Divisions: Critics argue that the caste-based census might reinforce caste identities, potentially deepening social divisions. For instance, caste-based data collection could lead to more rigid categorization and reinforce negative stereotypes. This could perpetuate societal tensions, as seen in some instances where the emphasis on caste has sparked conflicts or division within communities, instead of fostering unity.

- Focus on Caste Over Development: Some argue that focusing too much on caste could detract from addressing more universal issues, such as poverty, healthcare, and education, which affect people of all backgrounds. For instance, the emphasis on caste may overshadow the fact that many communities, regardless of caste, still face severe poverty and lack access to basic services. Critics point to the need to focus on more comprehensive, development-driven solutions that do not emphasize caste divisions.

- Inaccurate Representation: There are concerns that caste-based data may not be entirely accurate, as caste identities are often fluid. For example, many people may not clearly identify with a single caste or may choose not to disclose their caste due to social stigma. This issue arose in the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC), where there was significant inflation in the number of caste names reported due to the open-ended format used. This could lead to skewed data and make it difficult to accurately assess caste-based disparities.

- Risks to National Integration: Some worry that a caste-based census could undermine national integration by fostering competition rather than collaboration among different groups. This concern is rooted in the fear that caste-based data could become a tool for political manipulation, where caste identities are used to rally specific groups against others. For example, political parties may exploit caste data to mobilize voter bases, which could exacerbate tensions between different communities, hindering efforts for national cohesion.